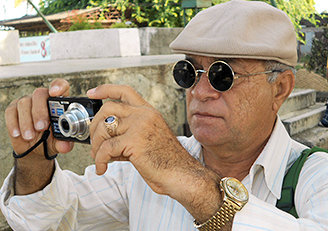

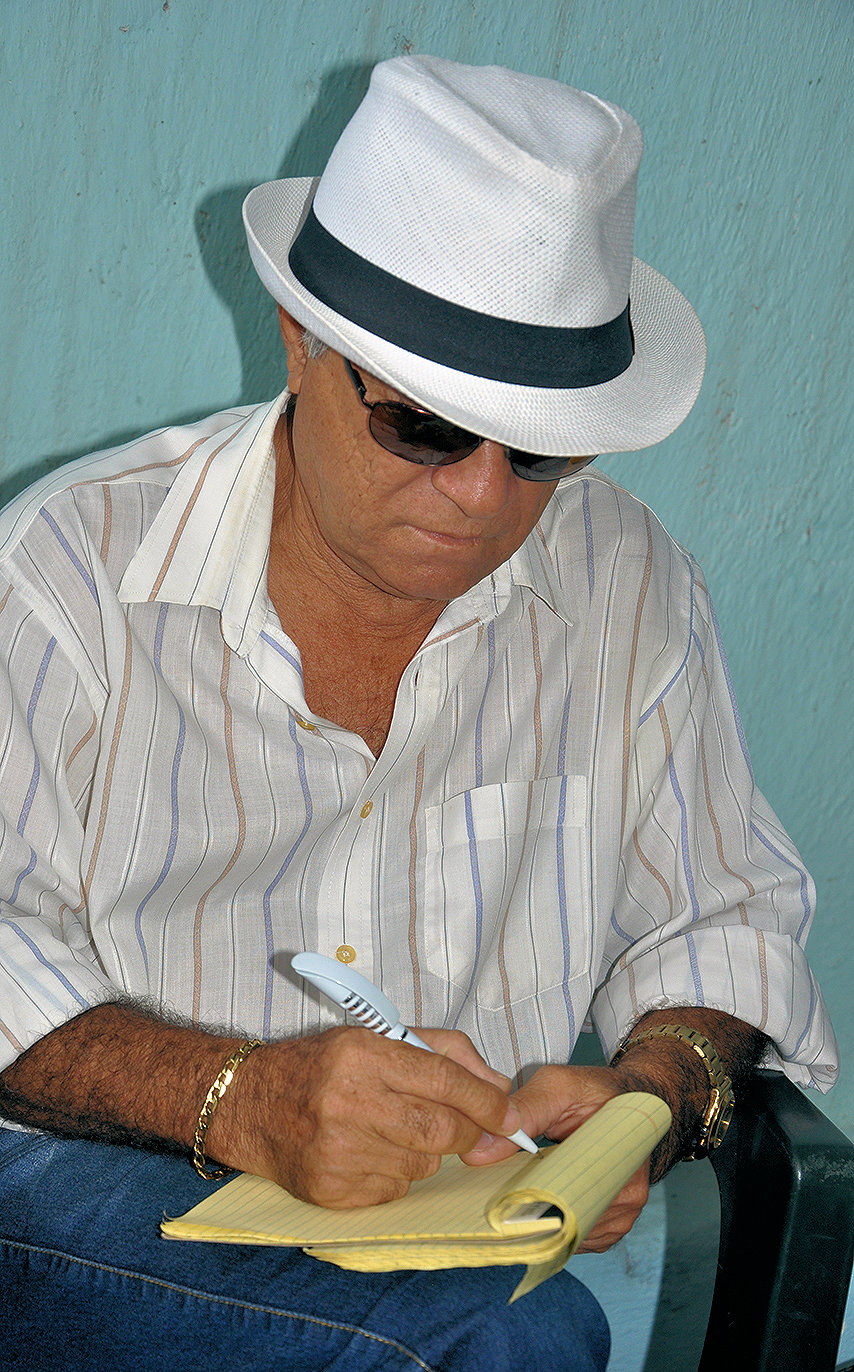

With Julio César Pérez Viera, one of those who forged the first pages of the newspaper 26, we begin this month of celebrations for our 45th anniversary. Follow our digital platforms and the next editions of the weekly to know, in the voice of some of its protagonists, the history of Las Tunas print media.

It was worth the same the guardrail flooded in dust, with the annoying pebbles forcing to zigzag between the caution and the sun, beaten in the right side of the face, that the chinks of mud in the surroundings of Chaparra. Any scenario seemed practically "unfeasible" for the journalist who germinated from Cascarero; but there was no force capable of leaving him dressed when he closed the penultimate button of the impeccable shirt that still protects him, 50 years later.

It was a luxury show. He tells that he helped his grandfather to provide him with a wheelbarrow to move the Tesla tape recorder, a "contraption" difficult to move, and with it to transmit any event or cultural activity of those places. He towed the "scaffolding" behind the bicycle and there were many times when, in front of the crowd, the equipment was out of tune and there was no way to record it.

Asking for Julio César Pérez Viera, then, led to an acclimatized office, like a community radio station, in Chaparra, where every day from 6:00 to 6:30 pm the events of that rural area were transmitted. Radio Libertad broadcasted the debates in which he always used his distinctive tone: criticism and he recalls that that half hour was so important that "there was no one more popular throughout the length and breadth of the sugar cane fields in bloom."

With a hint of funny, he confesses that one night, in 1972, his brother Luis asked him if he was interested in a course to become a journalist that they were starting to offer. Agitated to help his grandparents, he said yes, and at dawn, he went to see Juventino, who historically distributed the press in the Menéndez region, and asked for the position of assistant, but the man assured him that no one was needed there.

Then he learned that his relationship with journalism would be somewhat more intimate. The course was serious! He grabbed his wooden suitcase, threw in some clothes, and came to Las Tunas to become a reporter. Rossano Zamora Paadín dictated the first notes in his discreet little notebook. A month later he returned to Chaparra as head of the Information Center and a little later the "Tesla" came into his life.

FROM THE DAWN OF 26

"At that time Freddy Pérez Pérez was a volunteer correspondent in Delicias. Every day we learned something new and reported from the mountains. In that context, El Cañazo was born, a critical bulletin in which we reported on the state of the milling, planting, and cutting of sugarcane. No one escaped... That was my best period as a journalist, without being one...."

"At that time Freddy Pérez Pérez was a volunteer correspondent in Delicias. Every day we learned something new and reported from the mountains. In that context, El Cañazo was born, a critical bulletin in which we reported on the state of the milling, planting, and cutting of sugarcane. No one escaped... That was my best period as a journalist, without being one...."

In 1978 they put together a team of reporters and concentrated on the current Cuban News Agency. In that challenge rested the dawn of the first newspaper that was born with the name 26.

"It seems to me that I was looking at the machine in which the newspaper was edited: a piece of junk that nobody knew where it had come from. We were barricaded like in a country school in Victor's little hotel, a building located in the current specialized butcher's shop, and to work it was said, because those sheets had to be filled every day."

"It was a beautiful period, full of motivation and desire to learn. Making the newspaper was a feat that was achieved letter by letter. That birth was one of the greatest inspirations I had in my youth. Then came the linotype and the process was even more beautiful. I remember that all of us kids would wait on Colón Street until midnight to have the printed edition firsthand and enjoy the smell of the copies."

"Over the years, the group became a family and I never tire of saying it, it was the group in which I felt the best. The names became indispensable: Justo Vega, and Roberto Escobar, who was a young boy when he started working with great modesty, simplicity, and a loyalty to his friends that has never changed."

"I see us still there, in the new premises that was the current Radio Victoria radio station. Oscar Góngora's (el brujo) witticisms were born there to liven up the work. The collective was a 'shotgun': Roberto Doval, Freddy Pérez, José Infante, Juan Soto, and Nelson Marrero, who served as deputy director and was the teacher of all of us."

"Zamora Paadín was the head of Information and gave us the 'belt' when we messed up. He would give me a tremendous spanking for the leads, the order of prominence, the very large paragraphs, but afterward, in the afternoon, he would hug me and everything would be fine."

Even if he jokes about it, Julio recalls that he received rigorous preparation and much help from his most experienced colleagues. At the same time, he studied at the University of Santiago de Cuba and gained the confidence to fly over the horizons of his sectors, which were the Ministry of the Interior, the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution, and other political and mass organizations.

"IF WE'RE GOING TO TELL IT LIKE IT IS"

"I remember my first big scolding, which even led to a public reprimand. Juan Emilio Batista Cruz, at the head of the Sports Section, had left on a mission and the responsibility fell on me to fill more than half a page every day. It was tremendous and there was no rest."

"I was always running around. That day, José Gómez, a 'Colombian' boxer, won the World Boxing Championship and it was an important event. I was in a hurry and I told Miriam, the archivist, to do me a favor and look for a cliché (a kind of stencil in which the photos were printed on metal) of some dark-skinned because in the end, the printing of the newspaper was very bad and the photos almost invariably looked like a smudge, without distinguishing faces."

"I wrote a decent note and the next day my recognition of the boxing champion was published, accompanied by a photo of Domingo Urrutia, National Hero of Labor, cutting cane and with a print so clear that even the teeth could be distinguished. José Infante Reyes, the director, wanted to kill me, and it was not for less."

"Then Juan Emilio returned and I went back to my work. I can't forget the political act in Puerto Padre, which I had to cover. At that time, I had no car and I had to go in whatever I could get. I arrived early in the morning, but I had to turn around. No leader wanted to bring me and I showed up at 8:00 pm at the newspaper."

"They wanted to scold me, but no way. As luck would have it, Faure Chomón, secretary of the Cuban Communist Party at that time, went to check the printing and there I told him what had happened. He promised that he would have an answer and yes, from that day on, reporters were given more consideration and respect than we deserved. From the greeting, the snack, and lunch together, without distinctions."

"I confess that I had a predilection for critical work and that's why I got into a lot of trouble. I was taken every week to the Party for an analysis and the truth is that when they didn't send for me I felt bad. I had legendary troubles, such as the one that originated by a report on the Constructive Maintenance Company, in Puerto Padre. I proved that they had paid for works that were never built."

"From there I learned that you always have to leave 30 percent of the investigation, the most problematic part, for when you are called to tell. I remember that this material had a reply and I finished it off with a powerful counter-reply because I had prepared myself for that. A journalist must be first and foremost an investigator and cannot be afraid."

"Later, I wrote Ya comenzaron mal (They already started off badly), another report on the construction of the La Blanquita market on top of a small stream, I have the satisfaction that the project was corrected. A manager of the sector baptized me with the name of 'lengua de taladro' (drill tongue) and I was praised for that, although he was sanctioned for disrespect."

"I suddenly gained popularity, even though I wasn't looking for it. The best work I did came from the comments of ordinary people who stopped me on the street and told me their problems. I should clarify that I was writing for them. My biggest critics and the first two proofreaders I gave to read my proposals were Robertina, the cleaning lady, and Luisito, the chauffeur."

It was not in vain that he deserved to become a correspondent for the Granma newspaper, a responsibility he assumed with the same desire to tell stories with which he continued writing for his local newspaper.

BEHIND THE THRESHOLD OF RADIO

"I came to the radio station almost forced. I have always had my responsibilities with the Young Communist Youth Union and later with the Party. In the middle of the Special Period, I was called to support the expansion of Radio Victoria's 24-hour programming and I said yes. I had to take a step forward since militancy had its weight. I went with Miguelito, Rosita Velázquez and Wálner Ortega. Of course, the station ends up making anyone fall in love with it."

"I came to the radio station almost forced. I have always had my responsibilities with the Young Communist Youth Union and later with the Party. In the middle of the Special Period, I was called to support the expansion of Radio Victoria's 24-hour programming and I said yes. I had to take a step forward since militancy had its weight. I went with Miguelito, Rosita Velázquez and Wálner Ortega. Of course, the station ends up making anyone fall in love with it."

"I learned a lot, as in my first school at Radio Libertad. I even served as head of information and saw talented people develop, grow and make history."

"I came to Radio Progreso on my initiative. One day I met Misael Enamorado, secretary of the Party in the province, I proposed to him to create the correspondent's office and he gave me an open letter. I went there to negotiate with Andrés Mazorra. The position did not exist and they created it. Twenty-five years have passed since then."

"I am the founder of the correspondent's office, with all the time, affection, and commitment that this entails. I retired in December 2021 and a few months later the director of Progreso invited me to return and I came back. There is still a lot to say..."

BETWEEN JOURNALISM AND LIFE

He is the youngest of five siblings and was spoiled by his grandparents, with whom he lived since he was a child. He assures that from his grandmother (Mamita) Fidel Castro must have learned the phrase "Here you don't give alms, you share". He was trained as an elementary school teacher because he could not evade the call of the Homeland. He worked for free, for one year, and when he turned 18 years old he received his pay retroactively. The salary was 86.00 pesos per month.

He says that with journalism love was at first sight. He jokes about his small size, the same height with which he likes to face... And the "legend" is passed on from generation to generation that he defended the sector when a high leader of the country asked in a pejorative and repeated way what the press produced.

He boasts of having interviewed Fidel Castro Ruz three times. He has a compilation of his life's awards, international, national, and provincial, and I am sure he could not list them all. I highlight The Radio Microphone, Journalist of Merit, and the Lifetime Achievement Award.

But his voice is intoned when he speaks of his own, and his pride in his six children is almost tangible. His troop includes doctors, technologists, housewives, military personnel, and chess players. Nor the clean look of his wife, the laughter of his granddaughters, or the desperation of his dogs.

He walks the streets without haste because there, on every sidewalk, is the topic of the afternoon's commentary. A certain colleague once praised him for his ability to overcome obstacles being the son of a coalman, but Cascarero continues to be in Julio's eyes, as well as his Tesla tape recorder and the blank pages of 26. He has grown so big in the "carvings" that it is difficult to decipher whether journalism eclipsed his existence, or whether he became a reporter.