The forum Along the Paths of Song And Verse was developed on Twitter, which became an opportunity to delve into important issues for the preservation of the campesina tradition.

A total of 14 works representing Havana, Mayabeque, Matanzas, Sancti Spíritus and Las Tunas, were presented at the meeting, which contributed to expanding knowledge of the participants and users, in general, about this segment of the heritage, said Leticia Fernández, a specialist of the El Cucalambé Ibero-American Center of the Décima.

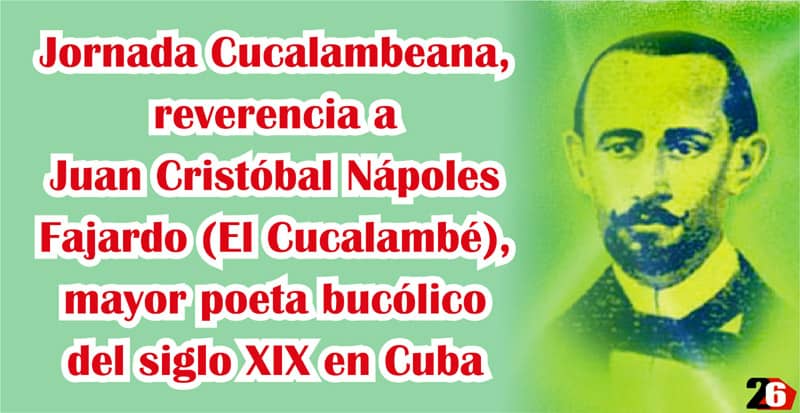

Through the Cuca2020 account and with the hashtag #PorLosCaminosDelCantoYElVerso, topics such as the life and work of Juan Cristóbal Nápoles Fajardo (El Cucalambé), the greatest bucolic poet of the 19th century in Cuba and others related to the tonadas, the Cuban point and some of its notorious cultists.

Through this interactive space, the Internet users were able to participate not only by sharing the publications and liking them; allegorical questions were also asked such as: Is the immaterial peasant culture of today a reflection of the reality of the Cuban fields?

In the materials disclosed in this digital platform, the importance of repentismo was discussed as a poetic and popular expression that is part of the nation's intangible heritage. Interesting elements about the consolidation of the Cuban point through the Canary emigration to Cuba were also disclosed.

Another topic on the agenda brought us closer to the work of cultists of Cuban traditions such as Cecilio Pérez Martínez, the “Guambán de la Música Campesina,” a singer with great musicality and anthropological character. Likewise, we expanded our knowledge about Orlando Laguardia Oramas, poet, singer and improviser, author of momentous works such as The strings of my Guitar and The new life.

Of course, the excellent literary work of the author of Rumores del Hórmigo, was an indispensable section of this virtual dialogue. In her article El Cucalambé is Alive the bachelor Leticia Fernández, demonstrated that he not only was a prominent figure of the décima in the Cuban 19th century, but that his Creole stamp contributed to the formation of national consciousness.

For that scholar, he is still valid in the new generations of rhapsodists because he had the virtue of singing in his time to our peasants and Indians, speaking of "Homeland and freedom in difficult moments of oppression and censorship,” for "semantic and allegorical values of his poetry (…), elements that made his work preferred by the mambises of 68' and 95'.”

Undoubtedly, 191 years after the birth of “the singer of Rufina,” he is still living folklore, as the researcher Carlos Tamayo, the maximum biographer of El Cucalambé, affirms.