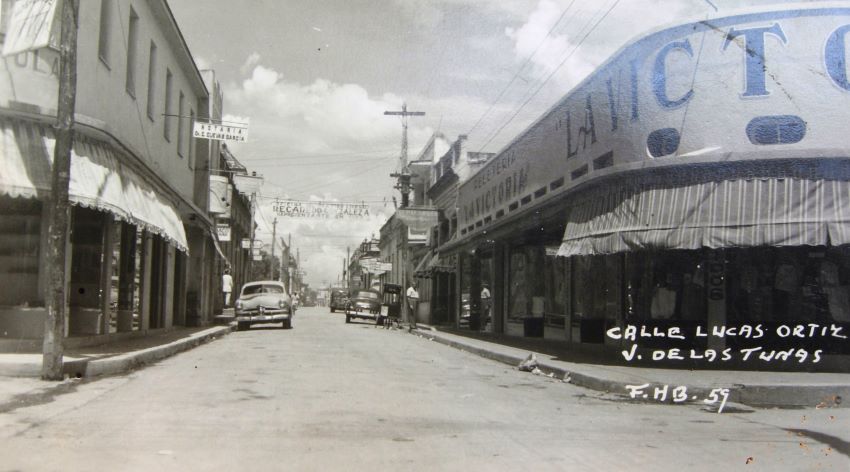

Lucas Ortiz Street, former Victoria de Las Tunas. |

It is said that back in 1603 there were already excellent conditions for the breeding and development of cattle in the Hato de Tunas. At that time, these lands embraced seven herds and eleven owners settled in the areas of Cabaniguán, Birama, Las Tunas, Unique, Ochoa, Las Arenas, and Aimiquiabo.

The place was becoming favorable for the settlement of neighbors from Bayamo, Manzanillo, Holguín, and Puerto Príncipe, and by 1761 there were already 40 families registered here. But, in the opinion of history, it is around 1796 that a foundational will for these places can be asserted. Poking around in the Municipal Ordinances of the Faithful People of Las Tunas, in force since January 1, 1860, and published months before in book form in the printing house of El Hórmigo, in the street De la Cruz Verde, number four, you discover many singularities that were word to fulfill at that time.

They constituted the regulatory body of the organization, administration, and provision of public services of a municipality; and, in the light of the 21st century, they are documents that allow us to approach the life of that time through these streets, the provisions, customs, and daily life that marked the passage of people and their dreams. Invitation of 26 on the day that our capital city celebrates its 227th birthday.

Building of the Central Highway, 1930. |

These texts explain that the limits of the land were to the north, the pasture, the tile field, and the savannah of Santo Domingo, property of Don Ángel Montes de Oca; to the northeast, the savannah and the forest of Bázaro, property of Don Vicente Salgado; to the southeast, the savannah of Viajaca, the Ahoga Pollos stream and Ramón Ortuño's ranch; in the southern corner, the property of Don Pedro Virella and to the southwest, the line formed by the entire course of the Hormiguero River.

Such norms prohibited working on Sundays, except with permission of the ecclesiastical authority first, and of the lieutenant governor of the district, later; on the day of the patron saint of this population and its eve, all the neighbors of the houses by were the procession passed were forced to clean the front of their houses and to put decorations with hangings in the doors and windows, and to illuminate the facades in the nights.

Community Mass in front of the parish church of St. Jerome, 1920. |

It was also forbidden to use copper vessels and utensils in the bodegas, botillerías, cafés, confectioneries, sweet shops, taverns, dairies, inns, and any other establishment where food or beverages were prepared. In the well-known "hot season", as they like to specify, it was obligatory to sprinkle the front of the houses with clean water twice a day; the first time, before 8:00 in the morning and then, in the afternoon, between 5:00 and 6:00; and that, taking care that the dust disappeared, but without allowing puddles to form that would bother the passage.

It was against the law to place the height of passers-by certain products in the stores, such as leather, which could cause anthrax and other dangerous diseases; the caretakers of children and the masters of slaves needed to vaccinate them when they were 6 months old, without delay.

Colón Street, former Victoria de Las Tunas. |

As far as dogs were concerned, it was illegal to whip them for fights or to make them bark at someone passing by. To take care of them, it was required to keep a pot with water in the threshold of the cellars and cafeterias for them to drink when passing by; those that walked on the street alone, without owners or a muzzle to identify them, were tied up.

In addition, no objects could be placed in doorways during the rainy season, so that passers-by could take shelter without great problems. Likewise, at any time of the year, anyone who dared to wear a costume belonging to a different sex or social class ran the risk of being prosecuted in court, if the object of the disguise was considered criminal.

Vicente García Park, 1930 |

Each one of these legislations, of which we have just shared a few, was punished with fines ranging from 2.00 to 25.00 pesos; they covered issues related to political life, religion, health, public order, supply, buildings, spectacles, and other related matters. All traces of what was once understood as a civilization, "correctness" or law.

Much has rained since then, and many have been the vicissitudes, throughout the centuries, of those who inhabit this region of cactus, which today refuses to forget itself and urgently needs dissimilar efforts to rediscover the path of success. It would be good for it to have several, inspired by the splendor that should not lose its portals, full of yesteryear, and the joy that has always been the excuse of its hard-working and noble people.