Doctor in Pedagogical Sciences María Gertrudis Batista Ortiz confesses that she measures her words more and more carefully.

If at the age of 12, a shout of "be careful!" saved the unrepeatable García Márquez from being run over by a bicycle and made him certain of the power of words, it has taken this woman more time, but just the enough to weigh the value of words, whether spoken or written.

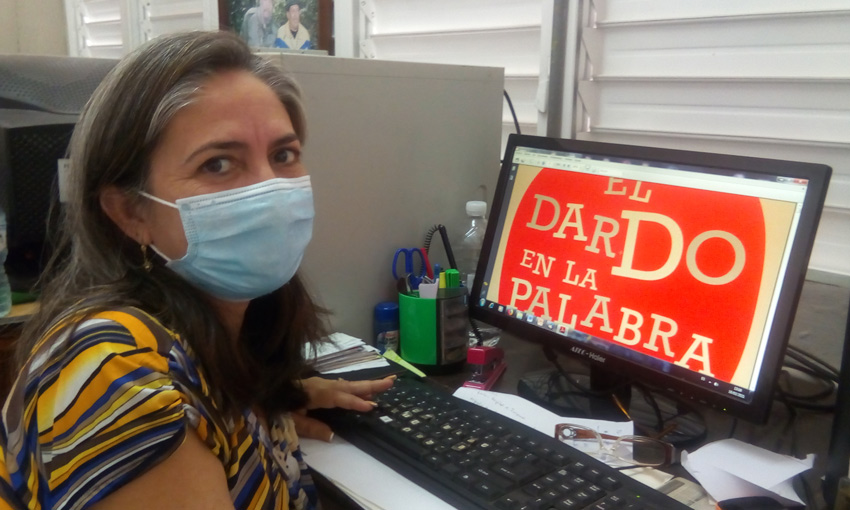

So, when she discovered those arrows that weigh down the language and which were masterfully analyzed by the academic Fernando Lázaro Carreter in his book El dardo en la palabra (The dart in the word), she transformed her vision of the Spanish language that she shares with some 500 million speakers on the planet.

"We Cubans are very fortunate to speak the Spanish language, the language of Cervantes," expresses the pedagogue and also director of International Relations at the University of Las Tunas.

"It is a very limited vision to see the language only as a means of expression or communication because it also becomes a symbol of identity, hence the unavoidable need to preserve it as well as other national symbols that make us unique," she emphasizes and then summarizes the distinctive features of the Cuban variant within the linguistic unity of the Spanish-speaking community. Spanish is one among equals, and therein lies the fortune that we sometimes fail to appreciate.

María Gertrudis Batista talks about the impact of new technologies on Spanish. She considers that they have contributed to generate a digital language, in parallel to the everyday one. She does not condemn, she knows that it is a daily construction, each individuality and society contributes.

"Technologies have become part of our lives and we must see them with a view to the future. For me, they have come to enrich our language, because they have allowed words to be incorporated due to the dynamics and technological development itself."

"Someone might be thinking about the messages we send by WhatsApp or SMS when we shorten words, use symbols or employ, sometimes, a single letter to mean some specific word or refer to some particular term. This is under investigation because for many linguists it is a parallel language that has arisen, of course, by the very use of these technologies."

"If it is good or bad... I don't think it is a wise decision to start from one side or the other or to be on one side or the other. Rather, we should take a holistic and integrating look at how we can take advantage of it. I do not think it is negative or even good. We have to look for the right measure of what we gain and what we lose."

The media must be champions of the art of correct speech, she says: "They have a high responsibility to communicate and a proper reading, a good diction or a correct pronunciation will allow the listener to have a paradigm of good speech."

As a teacher, she does not neglect the training of future educators and when referring to academic instruction, she highlights, in the curriculum of the Spanish Literature program, the discipline of History of the Spanish Language.

"It is a subject that provides students of our specialty with the tools to explain linguistic phenomena that occur in our language. This subject covers topics from the arrival of the Romans to the Iberian Peninsula, the formation of Spanish from Latin, its evolution in this geographical area, the arrival to the American continent, to Cuba, and how it manifests itself in the different ways of speaking in the country."

She has the absolute conviction that only if you read it will you go far or further. The intimacy with the work and the author generates "gains" to the reader of inestimable value, she expresses and emphasizes the need for students to appropriate this knowledge and appreciate the richness of a language whose peak is, perhaps, in literature.

"The coming of age of our language is reached with the work of Miguel de Cervantes, El ingenioso hidalgo don Quijote de la Mancha (The Ingenious Hidalgo Don Quixote of La Mancha), it is the masterpiece of Spanish"; she emphasizes to then ponder the value of the literature created in the cradle nation of "El manco de Lepanto," or of the literature created in Latin America and the Greater Antilles. She lists, then, the trail of Lorca, the novels of the land in the American continent, the Garcia Márquez creation...; and already inside the Island, authors like Guillén, Onelio Jorge Cardoso... and, in Las Tunas, El Cucacalambé and Guillermo Vidal, exponents of the writers that distinguish us.

"Language is identity, it is a symbol that identifies us as a nation. Let us save Castilian, let us be ecologists and preservers of a language that is one of the most beautiful in existence, not because it is ours but because of all the cultural richness it contains," she expresses with fruition before sharing one of Lázaro Carreter's reflections to which she owes -as the creator of magical realism owed to that savior priest- having discovered the power of words.

"All in all, what difference does it make, if we understand each other! Well, it does. First, because the language is not ours: we share it with many nations, and to break it to our own liking is to break the only firm thing of our fortune. Second, because we think with the language; if we use it badly, we will think badly; and if we change it, we will think like those with whom we would not like to think. Third, because exercising freedom, in this as in everything else, does not consist in letting go, but in knowing and being able to go. Purism impoverishes languages; casteism makes them rancid. Only free idiomatic trade favors the march of society to the rhythm of time."